■ When Your Patient Commits Suicide: The Psychiatrist’s Role, Responses, and Responsibilities

Psychological Autopsies

Stephen M. Soreff, M.D. (2)

- Director, Consultation and Liaison Psychiatry, Medical Center of Delaware, 15 Omega Drive, Building K, Room 206, Newark, Delaware, 19713.

- Director of Psychiatric Quality Assurance/ Medical Risk Management, Westborough State Hospital, 288 Lyman Street, Westborough, Massachusetts, 01581 and Lecturer in Psychiatry, University of Massachusetts Medical School, 55 Lake Avenue North, Worcester, Massachusetts, 01655.

Suicides constitute a not infrequent event in a psychiatrist’s practice

Suicides constitute a not infrequent event in a psychiatrist’s practice

and have a major impact upon the clinician as well as the family and the staff.

Many psychiatrists especially those in residency are never taught how to manage a patient’s suicide. The authors share their experiences in this area and make clear recommendations for interventions with staff, family, and other patients. Careful attention to the physician’s own needs are suggested. It is suggested that this material be made part of psychiatry residents training.

Introduction:

Suicide stands alone as a most powerful, indelible event. Despite years of training and research, the thought of a patient successfully committing suicide continues to strike fear in the hearts of a physician (4,11,16). Yet, if a psychiatrist is in practice long enough, it is reasonably likely that the practitioner will have a patient commits suicide. Chemtob reports that in their national survey, 51% of the responding psychiatrists had had a patient who committed suicide (1). Patients with an affective disorder have a suicide rate of 15% and those with schizophrenia have a suicide rate of 10% (17). In spite of the frequency of this event it remains a difficult area to discuss.

A patient’s suicide is even more potentially devastating when a psychiatrist experiences it during training (2,3). Brown found that 33% of psychiatric residents had had a patient commit suicide during their residency (2). He noted the resident’s vulnerabilities during training and of those who had had the experience of a patient suicide, 77% felt the impact to be ‘severe’ or ‘strong’ and 62% found it to have a ‘major effect’ on their development (2). Yet, rarely in our residency are we specifically taught how to handle a completed suicide. Mentors infrequently discuss their own encounters in this area.

Perhaps, even more devastating is when the doctor-to-be experiences a such medical school. Krueger discusses the impact of such death on a medical student and colleagues as well as ways of dealing with its repercussions (25).

Lindermann (5), Caplan (6) and Silverman (7) have emphasized aid to survivors of death scenes. They partly base their intervention on the premise that bereaved experience a higher risk of morbidity and mortality than those without such a loss. Ness and Pfeffer found the survivors of a suicide at a particularly significant jeopardy (21). These family’s sustain a great sense of shock, engage in protracted search for an explanation, have difficulty in talking about the loss, show prolonged feelings of guilt, and become very isolated. Additionally, the family members themselves are at an increased risk of suicide.

A growing number of doctors are dealing with the terrible loss of a patient to suicide. Feelings of guilt, fear, humiliation, rage, and more may plague a provider even years later.

Shneidman coined the term “postvention” to describe those activities that serve to reduce the aftereffects of a traumatic event (8). He emphasized the importance of intervention after the suicide.

Still, there remains little in the literature to guide physicians in their own conduct during the highly stressful moments, hours, days, weeks and months that follow a patient’s suicide (14,15,16,22). This paucity of procedure and protocol information can prove particularly unfortunate as the psychiatrist and the other survivors wrestle with feelings of shock, anger, a search for an explanation and a sense of quilt (21).

This paper offers guidelines and recommendations to the psychiatrist especially and to any psychotherapist generally who sustains the loss of a patient by suicide. Both authors have treated patients who committed suicide during or shortly after their psychiatry residencies. Using experience gained in managing these cases we will outline some of the steps useful in managing the complex issues that arise when a patient commits suicide. Although each patient, situation and clinician is unique, nonetheless, certain questions, issues and events arise that are universal.

Postvention

It is important to emphasize that any time a patient commits suicide it is a very personal event. Although many suicides will share themes, it is critical to be sensitive to the nuances of “your” case and to choose the appropriate postventions accordingly. We have organized postventions into five categories: the family, the staff, other patients, risk management and yourself. Many of the postventions will take place simultaneously. Nonetheless, the categories we have chosen provide a useful framework in which to conceptualize possible postventions.

Family:

The psychiatrist should personally contact the family as soon as possible. Whenever feasible the contact should be in person and in a quiet and private setting. Allow the family as much time as they need to ask questions and to begin grieving. Be open with your feelings about the event and loss. Your sharing may help them to discuss their feelings.

It is important to tell the family realistically that all that could have been done for the patient was done. For example, it is of solace to the survivors that the paramedics “valiantly” tried and the trauma center used “heroic efforts” in attempt to save the patient. It is also significant to tell them of all the treatment efforts on behalf of the patient that had been provided prior to the suicide.

Each family member will respond uniquely to the death. Sometimes the family seem in a hurry and want to end the discussion quickly. Here there is often a value in helping them to talk about their reactions. At other times, family may be quite open and emotional. Just being present is enough for the first meeting. Take them “where they are at” yet set an example and tone that “everything can be discussed.” Give them “permission” to grieve, to feel pain, sadness, anguish, and anger.

It is frequently valuable to wonder with the family if the suicide had been in some way been expected. A particularly useful question to explore with family is if they had any feelings that the patient would attempt and/or eventually succeed with suicide. Some family often “felt” you were going to tell them about the suicide even before you have told them anything. Families also “knew” from what the patient had said and done in the past that the outcome might be fatal.

Before ending the family meeting, the psychiatrist should do several things. First, let them know how they can reach you. Second, inquire as to their expectations from you for the immediate future. This might include setting up another meeting, discussions about wakes and funerals, memorials, donations and cards.

The family will usually guide you as to the appropriate duration for contact but we suggest that contact should last at least through the funeral and until the autopsy results are available. Psychiatric referrals are often indicated. Involving the clergy early on is perhaps one of the most productive postventions. They are skilled in these issues and can provide essential support. Remember, religion can provide answers that medicine/science can not.

A natural death is often painful and difficult for a family to deal with but a suicide can be devastating, overwhelming and extremely difficult for the survivors. An important part of your job is to acknowledge to the family that the grieving process may be much harder, more complex and more painful than for other deaths (21). “The survivor victims of suicidal death are saddled with an unhealthy complex of emotions: shame, guilt, anger, perplexity” (8).

Encouraging the family to ask the local media to respect their privacy and grief is often successful. Most newspapers will not report an obituary twice. Therefore, if the family purchases the obituary the newspaper is far less likely to write a more explicit column. This is a valuable piece of advice. The family often awaits the autopsy with the same anxieties as does the psychiatrist. It may be helpful to meet with the family to discuss the autopsy report. Your availability, if only to interpret the medical jargon will be appreciated.

Staff:

You have an important responsibility to inform the staff of the death as soon as possible and help them process their feelings. In an inpatient unit one of the most difficult tasks facing a psychiatrist is notifying three shifts of staff about the death. The technique is not unlike that used with the family. Gather the immediate shift and available staff together and tell them as a group. It will also be important to instruct this shift how you want the remaining shifts notified. Avoid casting blame; allow for group support and venting of emotions. Hodgkinson depicts the staff’s bereavement and underscores their benefits from organizational structural support (22). Make staff aware of the agenda for dealing with the death when this information is available (time of funeral, memorial service, etc.).

There are a number of benefits for staff in attending the funeral and memorial services. Markowitz describes these in his article (13). Our experience is that families will not only accept you but will welcome you. The social worker who went to the funeral in one of our cases not only demonstrated the hospital’s concern for the family and was well appreciated by the family but was also able to share with the staff how things went. The team was concerned how the family was doing and would handle the funeral. As a psychiatrist who attended the funeral (N.K.) I felt welcomed and had the pleasure of learning more by hearing others talk about the patient.

The eulogy may introduce you to facets of your patient and his/her life about which you were unaware; so may stories you hear from relatives and friends. It is a sad but often true commentary, one comes to know a person better at the funeral then one did during his/her life.

Cards and donations may be made on a personal basis. In one of our cases the family asked for all donations to be made to a local mental health out-reach center. These gestures were warmly received by all and assured staff that their efforts were appreciated.

Why a person takes his/her own life is a very private matter. Commonly and often quite privately, each staff member will review every aspect of each’s interactions and actions prior to the suicide. Rarely is it our experience that someone did something that specifically resulted in the suicide. Nonetheless, some staff will feel personally responsible for the actions of the patient. This requires group support and processing and may take multiple meetings to understand. In one of our cases, the process of closure and healing was not complete until after a Grand Rounds presentation dealing with the issue one year later.

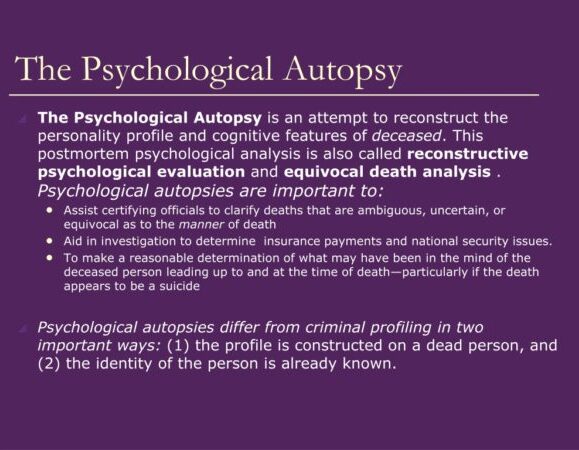

Psychological Autopsy

We strongly support the use of a psychological autopsy as described by Littman (18). A respected psychiatrist who is unfamiliar with the case should preside and notes should be kept. There are two clear purposes of the psychological autopsy. The first is as a cleansing exercise to allow all feelings to be aired openly. The second is to allow for policy reform, learning to come forth and for better patient care (24). Many institutions have a format for conducting a psychological autopsy as part of their policy and procedure manual. If they do not, we encourage them to develop such a format.

We strongly support the use of a psychological autopsy as described by Littman (18). A respected psychiatrist who is unfamiliar with the case should preside and notes should be kept. There are two clear purposes of the psychological autopsy. The first is as a cleansing exercise to allow all feelings to be aired openly. The second is to allow for policy reform, learning to come forth and for better patient care (24). Many institutions have a format for conducting a psychological autopsy as part of their policy and procedure manual. If they do not, we encourage them to develop such a format.

Again, although we stress the value of a psychological autopsy, as in all aspects of the suicide clinical judgement must be exercised. In some instances it may be better to delay the psychological autopsy for a period rather than do it right away.

Staff must also move on so that other living patients do not feel abandoned. Over time, the acuteness of the feelings will temper and both staff and patients will resume their previous routines.

Patients:

As mentioned above, a rapid, organized meeting of all patients with all staff (especially the psychiatrist being present) is crucial. Patients will have many feelings but especially important is their concern for the ability of the staff to help them when in their eyes the staff were unable to save the deceased. Hodgkinson also points out the increased vulnerabilities of patients at times of a suicide (22). They may not only be overwhelmed with a host of intense feelings, they may also be at some risk to act on their suicidal desires and impulses. Cotton in fact suggest canceling passes during the acute phase of the suicide and its aftermath (23).

Setting the stage by having both staff and patients share feelings is important and reenforces the sense of community of the inpatient ward. It is equally important to have people recognize the positive and negative aspects of the deceased, what they liked and disliked about the person. Patients may see staff as weaker as a result of a suicide and this too needs to be recognized. Decisions to keep the ward locked for an added feeling of security or to limit passes will similarly need to be addressed.

If the patient was an outpatient but involved in a group the procedures are much the same as for an inpatient setting. Here however, it is likely that the members will have heard of the death from the media or one another before the group convenes. It is important to make this the first topic of discussion at the next group session.

Patients may try to comfort staff in the group or alone in the subsequent days. It is important to see and to explore the feelings and thoughts behind such efforts. Similarly, some patients may intentionally try to devalue staff by continually reminding them of their “failure.” These efforts can stir negative counter-transference feelings which should be acknowledged and discussed in supervision.

Forensic Psychiatrist:

How and when you as a psychiatrist find out about your patient’s suicide influences your response. It will inevitably require interrupting other plans. If the patient is associated with a hospital or other facility it is important to promptly notify administration.

The next thing is to get some support for yourself. Take the time to contact a trusted colleague or mentor, preferably someone with experience in this area. It is likely that you will be unaware that they too have been through such an event in their career but the chances are good that they too have been in this position. Take a small amount of time to review the case in your mind and to reflect on the obvious questions that come to your mind about the patient and about your treatment.

The obvious thought of “where did I go wrong?” need not be perused at this time but at least acknowledge that it exists. Figure out the order in which things will need to be done and make a list to help keep you on track. In both cases, the support, direction and advice of senior attending psychiatrists proved invaluable in getting the resident through the night and the next few days. Ness and Pfeffer point out “with striking unanimity therapists have said that formal and informal consultation with colleagues is one of the most important and helpful actions to take in coping with a patient’s suicide” (21,pp 281)

Consider attending the wake and/or funeral. As explained above, the benefits are many. Most importantly, we feel that grieving needs to be done at least initially, in a group setting. This is the basis of the Jewish “sitting shivah” and the Christian wake. Trepidations that people will look at you askance when attending and holding you responsible for the death have in our experiences proved to be unfounded. Cards and donations are appropriate in most cases. As mentioned above, family will often embrace the idea that these can be targeted to help others with mental or emotional problems. “Contrary to popular belief, a statement of “I’m sorry this happened” is not an admission or responsibility and often soothes hurt feelings” (20).

You must be available for the staff with whom you work. You must share honestly and openly your thoughts and feelings about the situation. Being timely to rounds and meetings is critical. Your behavior will be interpreted by the staff and it must coincide with your words. It is important to remember your place on the team as both a member and as the leader. Others will follow your lead. Let the staff know that you are concerned for their welfare.

Attending the autopsy is strictly an individual choice but is not taboo. Psychiatrists are physicians. If the cause of death is equivocal, cooperation with the pathologist can help him/her decide this crucial issue. In some cases, particularly neuropsychiatric ones, the psychiatrist may have important information to share and also to learn.

A psychological autopsy should always be conducted. Both authors have taken part in them, as participants and as leaders, and attest to their usefulness in laying the case to rest. The atmosphere should be a supportive review. The focus should be less on “what did we do wrong?” and more on what can we learn from this and what can we do better.

An investigation will undoubtedly be conducted. Here, legal counsel should be consulted prior to any statements being given. It is your right to have counsel present at any and all questioning and depending on the case and the likelihood of suit this may be warranted. We suggest being conservative and involving counsel at all stages.

Billing the family for past services rendered is often a difficult task. Nonetheless, it may be the correct approach. To do otherwise might imply guilt (20). We are physicians. Fauman points that most patients and family equate outcome with the quality of the treatment (26). We can not guarantee an outcome whether it be in psychiatry, surgery or medicine. We bill for our time and our knowledge.

Moving on is important. Experiencing a patient’s suicide will create a lasting memory. Please, share your experience with younger clinicians, particularly those still in their training. Only through personal contact with a caring mentor can the delicate issue of patient suicide be addressed.

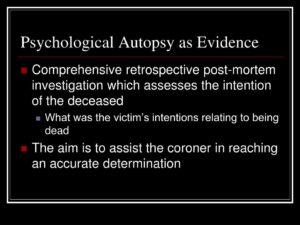

Psychological Autopsy as Evidence

Comprehensive retrospective post-mortem investigation which assesses the intention of the deceased – What was the victim’s intentions relating to being dead The aim is to assist the coroner in reaching an accurate determination

Risk Management:

Most institutions have a Risk Management Officer. This person’s job is to manage the problem from the hospitals end. Therefore, they will have the hospital’s and not your interest at heart. It is important to cooperate with them but being cautious is not unreasonable. Here an attorney may be a good idea. Also, the laws of each state will reflect to what degree you may be liable if a tort action should arise.

Risk management can help by controlling the press and hopefully keeping them away from you so that you can perform the various functions noted above as well as tending to the remainder of your patients. For you as an individual, notifying your malpractice carrier may be part of managing the risk however we feel this should not be done without first obtaining legal counsel and often will depend upon the setting in which you practice.

It is important to complete the medical record. Notes entered need to be dated accurately and should make clear that they are written after the death. Do not apologize in a note. Do not attempt to reason or justify decisions from a retrospective position. If your documentation and reasoning have previously been satisfactory there is little to fear.

Stick to descriptive language of the event and avoid drawing conclusions. Just explain the facts as you understand them to have occurred.

Conclusion:

Patients who commit suicide remind us of how impotent we often are in helping so many (10,11,13). Yet, if a suicide does occur, you as the treating psychiatrist have a role, a number of responsibilities, and responses. As the psychiatrist, you have a leadership position to the family and to the staff. You have responsibility of informing the family, working with the staff, communicating with the proper officials, and accurately documenting events in the record.

You as a treater, as a clinician, and as person have a number individual responses to the event and to the loss. You have the additional responsibility to yourself to get support. It is particularly difficult for a physician in this position to actively seek out the supervision and assistance of a more experienced colleague. Nonetheless, this can be invaluable in dealing with the aftermath of a successful suicide allowing the psychiatrist to learn from the death to be better prepared in the future.

References:

- Chemtob, C.M., Hamada, R.S., Bauer, G., et al, Patient’s suicides: Frequency and impact on psychiatrists, American Journal of Psychiatry, 145: 224-228, 1988.

- Brown, H.N., Patient suicide during residency training (1): Incidence, implications, and program response, Journal of Psychiatric Education, 11: 201-216, 1987.

- Brown, H.N., The impact of suicide on therapists in training, Comprehensive Psychiatry, 28: 101-112, 1987.

- Maltsberger, J.T., Buie, D.H.: Countertransference Hate in the Treatment of Suicidal Patients. Archives of General Psychiatry, Vol 30, 625-633, 1974.

- Lindemann, E.: Symptomatology and Management of Acute Grief. American Journal of Psychiatry, 101: 141-148, 1944.

- Caplan, G.: Emotional Problems of Early Childhood. New York, Basic Books, Inc., 1955.

- Silverman, P.: The Widow-to-Widow Program. An Experiment in Preventive Intervention. Mental Hygiene, 53: 333-337, 1969.

- Shneidman, E. S.: The Management of the Presuicidal, Suicidal , and Postsuicidal Patient. In: Ross, J., Hewitt, W., et al: Annals of Internal Medicine, 75: 441-458, 1971.

- Shneidman, E.S.: Death of Man. Quadrangle Books, New York, 1973.

- Littman, R.E.: When Patients Commit Suicide. American Journal of Psychotherapy, 19: 570, 1965.

- Kayton, L., and Freed, H.: Effects of Suicide in a Psychiatric Hospital. Archives of General Psychiatry, 17: 187-194, 1967.

- Wahl, C.: The Fear of Death. Bulletin of the Menninger Clinic. 22: 214-223, 1958.

- Markowitz, J.: Attending the Funeral of a Patient Who Commits Suicide. American Journal of Psychiatry, 147: 1 122-123, 1990.

- Sacks, M.: When Patients Kill Themselves. In Review of Psychiatry, Volume 8. Edited by Tasman, A., Hales, R., Frances, A. Washington, D.C. American Psychiatric Association Press, 1989.

- Goldstein, L., Buongiono, P.: Psychotherapists as Suicide Survivors. American Journal of Psychiatry, 138: 392-398, 1984.

- Soreff, S.: The Impact of Staff Suicide on a Psychiatric Inpatient Unit. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 161:2, 130-133, 1975.

- Kaplan, H., Sadock, B.: Synopsis of Psychiatry, Fifth Edition, Baltimore, Maryland, Williams and Wilkins, 1988

- Littman, R., et. al.: Investigation of Equivocal Suicides. Journal of The American Medical Association, 184, 924-929, 1963.

- Kunitz, S. ed., Poems of John Keats, New York, Thomas Y. Crowell, Co. 1964. pp 55.

- Strasburger, L.: Elderly Suicide Often Results in Litigation for the Treating Psychiatrist. The Psychiatric Times, 3/90, page 52, 1990.

- Ness, D.E., Pfeffer, C.R.: Sequelae ofe Bereavement Resulting from Suicide. American Journal of Psychiatry, 147:3 279-285, 1990.

- Hodgkinson, P.E., : Responding to In-patient Suicide, British Journal of Medical Psychology, 60, 387-392, 1987.

- Cotton, P.G., Drake, R.E., Whitaker, A., Staff Response to the suicide on a psychiatric inpatient unit, Hospital and Community Psychiatry, 34, 55-59, 1983.

- Flinn, D.E., Slawson, P.F., Schwartz, D., Staff Response to Suicide of Hospitalized Psychiatric Patients, Hospital and Community Psychiatry, 29:2, 122-127, 1978.

- Krueger, D.W., Patient Suicide: Model for Medical Student Teaching and Mourning, General Hospital Psychiatry, V?, 229- 233, 1979.

- Fauman, M.A., Quality Assurance Monitoring in Psychiatry, American Journal of Psychiatry, 146: 1121-1130, 1989.